Tuesday, June 24, 2014

Monday, June 23, 2014

Wednesday, June 18, 2014

Hasee Toh Phasee

Watching films at home has its own peril. Sometimes you tend to fast-forward a film, trying to get a grip, trying to figure out what’s happening, and you end up not liking the film, simply because you did not see the film in the sequence it was intended.

This exactly what happened during my first viewing of Hasee To Phasee. I found the film disjointed. I told this to a friend. He was beside himself. This is his favourite film of the year, so far. He has seen the film three times, in theatre. So, just to make him happy, I saw the film again, and this time I really liked it.

I am still not crazy about it, or about Parineeti Chopra, whom my friend likes so much. I thought her ‘drug-addicted’ sequences were a tad over-acted. I should know.

Otherwise, the film was a breeze, despite the fact that it centres on a wedding, the background for almost all Bollywood movies these days.

What I liked most was how the movie treats its minor characters, and there were so many of them (including a foreign friend, who even doesn’t get to dance, or did he? We do not really know who he was.). They do not have much screen time, but, somehow, like clockwork, the screenwriters find time to give each of them a fleeing second of glory. Including Tinu Anand. It’s fun.

And, after a long time, here is a film set in Bombay, not Delhi, or Europe.

This exactly what happened during my first viewing of Hasee To Phasee. I found the film disjointed. I told this to a friend. He was beside himself. This is his favourite film of the year, so far. He has seen the film three times, in theatre. So, just to make him happy, I saw the film again, and this time I really liked it.

I am still not crazy about it, or about Parineeti Chopra, whom my friend likes so much. I thought her ‘drug-addicted’ sequences were a tad over-acted. I should know.

Otherwise, the film was a breeze, despite the fact that it centres on a wedding, the background for almost all Bollywood movies these days.

What I liked most was how the movie treats its minor characters, and there were so many of them (including a foreign friend, who even doesn’t get to dance, or did he? We do not really know who he was.). They do not have much screen time, but, somehow, like clockwork, the screenwriters find time to give each of them a fleeing second of glory. Including Tinu Anand. It’s fun.

And, after a long time, here is a film set in Bombay, not Delhi, or Europe.

Tuesday, June 10, 2014

The Big Fix

Cricket is the country’s national past-time, and it is a wonder that so far no author has tackled this in a crime thriller (especially when there have been enough crimes in the game). Now, Vikas Singh’s The Big Fix fills the void.

The book is a classic thriller, involving a woman crime reporter and a police inspector, even though you feel that the twist at the end occurs very fast.

Another thing that sort of bothers you is the heroic quality of the male protagonist, the captain of the cricket team. Yet, you will find it hard to object to Singh’s choices, because of his almost infectious love for the game.

The book contains several scenes of the game actually being played on the field, with Singh giving us a blow by blow commentary, and the way it is written, it’s nothing sort of a miracle. He describes each and every feeling on the pages, so much so that you feel as if you are watching the game yourself.

Perhaps, that’s the reason why the author failed to dig deep into the crime aspect, which is, obviously, match-fixing.

The book is a classic thriller, involving a woman crime reporter and a police inspector, even though you feel that the twist at the end occurs very fast.

Another thing that sort of bothers you is the heroic quality of the male protagonist, the captain of the cricket team. Yet, you will find it hard to object to Singh’s choices, because of his almost infectious love for the game.

The book contains several scenes of the game actually being played on the field, with Singh giving us a blow by blow commentary, and the way it is written, it’s nothing sort of a miracle. He describes each and every feeling on the pages, so much so that you feel as if you are watching the game yourself.

Perhaps, that’s the reason why the author failed to dig deep into the crime aspect, which is, obviously, match-fixing.

A Strange Kind of Paradise

I read both the Sam Miller books, Adventures in a Mega City and A Strange Kind of Paradise, together. The first book was long overdue, and the second book was just out. I think I liked the second book better.

The first book sounds a little contrived; the author circling the city on foot. And, somehow, in the last few years, it has aged badly. The Delhi that Miller describes in the book has changed considerably. The Delhi I know is more complicated than described by Miller.

A Strange Kind of Paradise is, on the other hand, about foreigners’ love affair with India, right from Alexander to Chinese monks to Roberto Rossellini and Allan Ginsberg. There may not be much original research, but the book is a work of great scholarship, as Miller digs deep into the historical personas and events. For example, the portion on Nana Saheb, and how this hero of the ‘Sepoy Mutiny’ caught the fancy of the Europe (and became the model for Wells’ Captain Nemo). It’s well-researched and eminently readable.

However, what is the most interesting aspect of the book is how the author fuses his own life story with the stories of other Indophiles (I am not sure Indophile would be the right moniker.). There are traces of William Dalrymple here and there (Like Dalrymple, Miller too is a British, who has since made India his home), but I am sure that cannot be avoided when you are writing a book about India.

The first book sounds a little contrived; the author circling the city on foot. And, somehow, in the last few years, it has aged badly. The Delhi that Miller describes in the book has changed considerably. The Delhi I know is more complicated than described by Miller.

A Strange Kind of Paradise is, on the other hand, about foreigners’ love affair with India, right from Alexander to Chinese monks to Roberto Rossellini and Allan Ginsberg. There may not be much original research, but the book is a work of great scholarship, as Miller digs deep into the historical personas and events. For example, the portion on Nana Saheb, and how this hero of the ‘Sepoy Mutiny’ caught the fancy of the Europe (and became the model for Wells’ Captain Nemo). It’s well-researched and eminently readable.

However, what is the most interesting aspect of the book is how the author fuses his own life story with the stories of other Indophiles (I am not sure Indophile would be the right moniker.). There are traces of William Dalrymple here and there (Like Dalrymple, Miller too is a British, who has since made India his home), but I am sure that cannot be avoided when you are writing a book about India.

Ka

The New York Times Review By Sunil Khilani/

"It was as if everybody were suddenly tired of doing things that had meaning. They wanted to sit down, in the grass or around a heap of smoldering logs, and listen to stories.'' Roberto Calasso's gloss on the epic intricacies of the Mahabharata, the longest story in the world, might also stand as a caption to his own new book, sleepless in its storytelling. But we should not be disarmed, for the book, ingeniously translated from the Italian by Tim Parks, is equally quick with meanings.

The third in a planned five-volume work, ''Ka'' -- which the publisher describes as ''stories of the mind and gods of India'' -- follows the high torsion of ''The Ruin of Kasch'' (1996), which evoked the emergence of the modern from the collapse of the past, and the more languorous seductions of ''The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony'' (1994), which subsumed the whole of Greek mythology in a single meditation.

To read ''Ka'' is to experience a giddy invasion of stories -- brilliant, enigmatic, troubling, outrageous, erotic, beautiful. Yet ''Ka,'' like the two previous books, is not a novel. Calasso's form-defying works plot ideas, not character. A writer with philosophical tastes, he thinks in stories rather than arguments or syllogisms. The two epigraphs to ''Ka'' announce this style: Spinoza's remark that ideas are only narratives or mental figures of the real world and, from the Yogavasistha, a definition of the world as being ''like the impression left by the telling of a story.''

''Ka'' is the emotional and philosophical nub of Calasso's five-volume project. His acutely nominalist temperament finds its ideal home in the stories of India, especially those early stories of the Aryans, which affirm always the power and sovereignty of mind. As Atri, one of the seven rsis, or seers, of the Aryas (the people that migrated from central Asia to India and became the upper castes there), says, ''Every true philosopher thinks but one thought; the same can be said of a civilization.'' The one crystallizing insight of the Aryan intellect, as Calasso sees it, is that the existent world ''only exists if consciousness perceives it as existing. And if a consciousness perceives it, within that consciousness there must be another consciousness that perceives the consciousness that perceives.''

MORE HERE>

"It was as if everybody were suddenly tired of doing things that had meaning. They wanted to sit down, in the grass or around a heap of smoldering logs, and listen to stories.'' Roberto Calasso's gloss on the epic intricacies of the Mahabharata, the longest story in the world, might also stand as a caption to his own new book, sleepless in its storytelling. But we should not be disarmed, for the book, ingeniously translated from the Italian by Tim Parks, is equally quick with meanings.

The third in a planned five-volume work, ''Ka'' -- which the publisher describes as ''stories of the mind and gods of India'' -- follows the high torsion of ''The Ruin of Kasch'' (1996), which evoked the emergence of the modern from the collapse of the past, and the more languorous seductions of ''The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony'' (1994), which subsumed the whole of Greek mythology in a single meditation.

To read ''Ka'' is to experience a giddy invasion of stories -- brilliant, enigmatic, troubling, outrageous, erotic, beautiful. Yet ''Ka,'' like the two previous books, is not a novel. Calasso's form-defying works plot ideas, not character. A writer with philosophical tastes, he thinks in stories rather than arguments or syllogisms. The two epigraphs to ''Ka'' announce this style: Spinoza's remark that ideas are only narratives or mental figures of the real world and, from the Yogavasistha, a definition of the world as being ''like the impression left by the telling of a story.''

''Ka'' is the emotional and philosophical nub of Calasso's five-volume project. His acutely nominalist temperament finds its ideal home in the stories of India, especially those early stories of the Aryans, which affirm always the power and sovereignty of mind. As Atri, one of the seven rsis, or seers, of the Aryas (the people that migrated from central Asia to India and became the upper castes there), says, ''Every true philosopher thinks but one thought; the same can be said of a civilization.'' The one crystallizing insight of the Aryan intellect, as Calasso sees it, is that the existent world ''only exists if consciousness perceives it as existing. And if a consciousness perceives it, within that consciousness there must be another consciousness that perceives the consciousness that perceives.''

MORE HERE>

Custody

The Manju Kapoor novel must have been very difficult to write. To juggle among so many characters, even the minor ones, with conflicting points of views, and then to present them unbiased as complex human beings, is a task indeed.

It is a monumental achievement. Yet as you finish the book, you wonder if the second half of the book still needed some work, when the narrative goes to every direction, without warning.

The basic story is simple. A Delhi couple separates after the beautiful wife falls in love with the husband’s boss. Apart from the couple’s ego, what makes the matter complicated is the two young children. Thus, begins the battle for custody.

Finally, in her telling of the legal tangles and emotional turmoil of her characters, Kapoor tries hard to be impartial and she almost succeeds. And, how she portrays Delhi!

It is a monumental achievement. Yet as you finish the book, you wonder if the second half of the book still needed some work, when the narrative goes to every direction, without warning.

The basic story is simple. A Delhi couple separates after the beautiful wife falls in love with the husband’s boss. Apart from the couple’s ego, what makes the matter complicated is the two young children. Thus, begins the battle for custody.

Finally, in her telling of the legal tangles and emotional turmoil of her characters, Kapoor tries hard to be impartial and she almost succeeds. And, how she portrays Delhi!

City of Djins

The book that changed the face of travel writing in India, and spawned a large number of similar books on Delhi…

I was avoiding reading the book for a long time, because I knew I would have problems with it; the basic problem being the issue of the point of view, how an expatriate sees India. I was also apprehensive because the book was so well received.

Finally, after moving to Delhi, at the insistence of a friend, a picked up the book, and for most part I liked the book. I especially liked when the Dalrymple talks about his wife’s ancestors, and about the arrival of the British to Delhi after the ‘Mutiny’. There is real scholarship in these sections.

What I had problems with are the current description of Delhi, and the author’s own experiences. For one thing, the Delhi I know today and the Delhi Dalrymple paints is the book is very different. The city has changed considerably since the book was written. That’s one part of the problem. The second is the ‘fictionalisation’ of the accounts. I couldn’t, to save my life, believe the interactions the author describes in the book. I don’t have problems with fiction, but I have problems with fiction being presented as fact.

I was avoiding reading the book for a long time, because I knew I would have problems with it; the basic problem being the issue of the point of view, how an expatriate sees India. I was also apprehensive because the book was so well received.

Finally, after moving to Delhi, at the insistence of a friend, a picked up the book, and for most part I liked the book. I especially liked when the Dalrymple talks about his wife’s ancestors, and about the arrival of the British to Delhi after the ‘Mutiny’. There is real scholarship in these sections.

What I had problems with are the current description of Delhi, and the author’s own experiences. For one thing, the Delhi I know today and the Delhi Dalrymple paints is the book is very different. The city has changed considerably since the book was written. That’s one part of the problem. The second is the ‘fictionalisation’ of the accounts. I couldn’t, to save my life, believe the interactions the author describes in the book. I don’t have problems with fiction, but I have problems with fiction being presented as fact.

City Adrift

Writes Mumbai Boss/

We’d like to think that it’s only recently that Mumbaikars have expressed their unhappiness with their city so volubly and relentlessly. But Mumbai’s decline, its long time critics will know is not a recent phenomenon (“The housing famine is acute” huffed one citizen about Bandra in 1927). We’ve been on that trajectory for well over three centuries right from when the East India Company first leased the city from Charles II and saw in its swampy, malaria-ridden acres a strategically located port and trade route. It’s this path of decline, as warped as the course of the Mithi, that Naresh Fernandes charts in City Adrift: A Short Biography Of Bombay, a terrifically paced, terribly heartbreaking chronicle of the many times when the citizenry of Bombay very effectively screwed things up.

Fernandes’s tone is exasperated, angry even, that of a man whose love for the city has been ridden over roughshod just one too many times. He is obstinate too as when he stakes his right to call Bombay by its colonial name (until tellingly the very last line), because “the rechristening of the city is still remembered for what it is – a refutation of Bombay’s inclusive history”. If someone would like to come forth and defend Mumbai’s glories, then step forward please (unless you’re from the government), because as it stands, we have near none to claim anymore.

There is plenty to roil anyone living here – like when Navi Mumbai’s urban ambitions were thwarted in stupidity and shortsightedness to build Nariman Point; when crores were plugged into infrastructure projects like the Bandra Worli Sea Link that privilege a few. When mills are redeveloped in such higgledy piggledy nonchalance for the bottom line of profit, we are all but ensured a city of breathtaking claustrophobia. Today there are parks open to all situated, in a cruelly ironic twist, inside private mill compounds; few know they exist, fewer still ever see them. To wit: each of us living here has about 1.1 square metres of open space and that includes pavements and traffic islands.

MORE HERE>

We’d like to think that it’s only recently that Mumbaikars have expressed their unhappiness with their city so volubly and relentlessly. But Mumbai’s decline, its long time critics will know is not a recent phenomenon (“The housing famine is acute” huffed one citizen about Bandra in 1927). We’ve been on that trajectory for well over three centuries right from when the East India Company first leased the city from Charles II and saw in its swampy, malaria-ridden acres a strategically located port and trade route. It’s this path of decline, as warped as the course of the Mithi, that Naresh Fernandes charts in City Adrift: A Short Biography Of Bombay, a terrifically paced, terribly heartbreaking chronicle of the many times when the citizenry of Bombay very effectively screwed things up.

Fernandes’s tone is exasperated, angry even, that of a man whose love for the city has been ridden over roughshod just one too many times. He is obstinate too as when he stakes his right to call Bombay by its colonial name (until tellingly the very last line), because “the rechristening of the city is still remembered for what it is – a refutation of Bombay’s inclusive history”. If someone would like to come forth and defend Mumbai’s glories, then step forward please (unless you’re from the government), because as it stands, we have near none to claim anymore.

There is plenty to roil anyone living here – like when Navi Mumbai’s urban ambitions were thwarted in stupidity and shortsightedness to build Nariman Point; when crores were plugged into infrastructure projects like the Bandra Worli Sea Link that privilege a few. When mills are redeveloped in such higgledy piggledy nonchalance for the bottom line of profit, we are all but ensured a city of breathtaking claustrophobia. Today there are parks open to all situated, in a cruelly ironic twist, inside private mill compounds; few know they exist, fewer still ever see them. To wit: each of us living here has about 1.1 square metres of open space and that includes pavements and traffic islands.

MORE HERE>

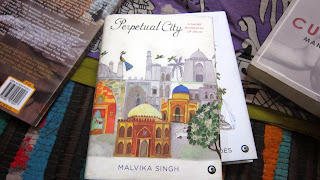

Perpetual City

The IBN Live Book Review/

The book is divided into two sections namely, perpetual city & changing city. In the first section, the author talks about Delhi right after the independence and how it was a legacy that had once been capital to successive empires. From Tomars-Chauhans, the Mamluks, the Khiljis, the Tughlaks, the Sayyids, the Lodis, the Mughals, the Nehrus, the Gandhis, the list has some heavy weight names who are responsible in shaping up the Delhi of today's times.

While describing the Delhi of 50s and 60s, the author paints a vivid picture of the city through her description about the city and how enchanting the city was.

Being is Delhi was all about experiencing the monuments, music and food of the city. This book is a part family memoir where Malvika Singh shares how her family and friends used to hangout together from the labyrinthian gullies of Old Delhi for late night food walks, Tughlakabad, Qutab Minar, Nizamuddin. Going to musical evenings at Siri Fort and how Delhi where Amir Khusro lived is a centre of qawwali, sufi music and poetry. Interesting and informative anecdotes from her life made the book rich in content and added various dimensions to it.

In the second section of the book, Malvika Singh talks about the Delhi and its evolution to become what it is today. Describing my favourite hangout place of Delhi, Connaught Place that used to a nice quaint place once upon a time transforming into a gigantic corporate and shopping hub of what it is today. How in the name of building infrastructure, many of the ancient buildings of historic significance were destroyed on the whims of politicians and babus for no rhyme and reason and a lot more.

The author also talks of the times when Late Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru was an accessible prime minister of the country, how much people loved him and the times after that when several other prime ministers took the seat and failed to deliver till Indira Gandhi came into the picture and how quickly things changed after her death. Corruption came into picture, corporate giants seeping into the city taking away its serenity and turning it into a metropolitan. How lives of people changed during the evolution and a lot more.

More Here/

The book is divided into two sections namely, perpetual city & changing city. In the first section, the author talks about Delhi right after the independence and how it was a legacy that had once been capital to successive empires. From Tomars-Chauhans, the Mamluks, the Khiljis, the Tughlaks, the Sayyids, the Lodis, the Mughals, the Nehrus, the Gandhis, the list has some heavy weight names who are responsible in shaping up the Delhi of today's times.

While describing the Delhi of 50s and 60s, the author paints a vivid picture of the city through her description about the city and how enchanting the city was.

Being is Delhi was all about experiencing the monuments, music and food of the city. This book is a part family memoir where Malvika Singh shares how her family and friends used to hangout together from the labyrinthian gullies of Old Delhi for late night food walks, Tughlakabad, Qutab Minar, Nizamuddin. Going to musical evenings at Siri Fort and how Delhi where Amir Khusro lived is a centre of qawwali, sufi music and poetry. Interesting and informative anecdotes from her life made the book rich in content and added various dimensions to it.

In the second section of the book, Malvika Singh talks about the Delhi and its evolution to become what it is today. Describing my favourite hangout place of Delhi, Connaught Place that used to a nice quaint place once upon a time transforming into a gigantic corporate and shopping hub of what it is today. How in the name of building infrastructure, many of the ancient buildings of historic significance were destroyed on the whims of politicians and babus for no rhyme and reason and a lot more.

The author also talks of the times when Late Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru was an accessible prime minister of the country, how much people loved him and the times after that when several other prime ministers took the seat and failed to deliver till Indira Gandhi came into the picture and how quickly things changed after her death. Corruption came into picture, corporate giants seeping into the city taking away its serenity and turning it into a metropolitan. How lives of people changed during the evolution and a lot more.

More Here/

The Battle of Algiers

Acts of violence do not win wars. Neither wars nor revolutions. Terrorism is useful as a start. But then, people themselves must act. … It’s hard enough to start a revolution, even harder to sustain it. And hardest of all to win it. But it’s only afterwards, once we have won, that the real difficulties begin…

The philosophy of a revolution, in Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (1966)

Paying for It

Paying for It is an autobiographical graphic novel by Canadian artist Chester Brown about his experience of being a john, visiting various prostitutes in the course of several years. Come to think of it, I think, only a Canadian could have written such a frank account, a book which has all the potential to be sleazy and pornographic, and also offensive, and which ultimately turns into a personal meditation on the nature of sex and love, and the whole business of prostitution.

The beauty of the book is not that it gives matter of fact commentary on sex, without being squeamish and scandalized, it also presents the girls Brown meets in the course of the book with rare individuality, yet protecting their identity.

For one thing, except for his former girlfriend, with whom he is not sleeping anymore, Brown refrains from drawing the faces of all the other girls he encounters.

/

The New York Times Book Review/

You don’t have to like comics to relish this book. Brown, whose previous work includes a comic-strip biography of the 19th-century Canadian revolutionary Louis Riel, begins his story in the summer of 1996, when his live-in girlfriend, Sook-Yin, confesses she has fallen for another guy. She also still wants to live with Chester. “I love living with you,” she says. Chester — feeling like his “normal, content, all-is-well-with-the-world self” — goes with the flow. (“You’re fine with this?” an astonished friend asks him. “I’m fine,” Chester replies.)

He and his girlfriend transition to being friends and housemates. A few months later, the new boyfriend moves in with them. Brown, still single, realizes he has come to a place in his life where he has “two competing desires — the desire to have sex, versus the desire NOT to have a girlfriend.” He seriously questions the idea of romantic love, and concludes it is a virtually impossible ideal. He decides to explore his options, which leads him to experiment with prostitutes. He finds some through brothel advertisements, and also online. “There are a whole bunch of these prostitute-review Web sites,” he tells a friend — johns writing for other johns, “like movie reviews or book reviews.”

Over the course of several years, Brown had numerous paid sexual encounters, and in “Paying for It” he has given each woman a chapter: Carla, Anne, Wendy, Yvette, back to Anne, Jolene, Larissa, Angelina, Kitty, Gwendolyn, Jenna, back to Angelina, Myra, etc. He also recounts conversations about his thoughts and motivations that he had with his close friends, some of whom disapprove (“There is NO way I’m paying for sex,” says one), others of whom are ambivalent (“I think it should be legal, but that’s not the same thing as saying it’s right”).

Chester Brown is not a john to pity. He has options. He is a reasonably handsome, lanky, talented artist, now 51 years old. Some women, and men, who read this memoir may develop a crush on this goodhearted bad boy. The cartoonist R. Crumb, who provides the introduction for the book, describes him as “a very advanced human.” Brown also seems to be a feeling, thoughtful, considerate man, honest with himself and others.

This graphic memoir is . . . sexually graphic. Chester’s penis is a leading character, and a charming one at that. Brown has made no obvious attempt to eroticize his drawings, and as a result his cartoons are totally sexy in the way real life and really good art are sexy. As he explores the logistics of being a john, he shares what he’s learned about hygiene, the etiquette of paying and tipping, and the necessary financial planning (“If I went every two weeks, that would be 26 times a year; 26 multiplied by $160 equals $4,160 a year — that’s quite a bit”). He also gratefully acknowledges the Canada Council for the Arts “for generously assisting me financially while I wrote and drew this work.” Can you imagine the National Endowment for the Arts financing any project remotely resembling this? O Canada!

MORE HERE/

The beauty of the book is not that it gives matter of fact commentary on sex, without being squeamish and scandalized, it also presents the girls Brown meets in the course of the book with rare individuality, yet protecting their identity.

For one thing, except for his former girlfriend, with whom he is not sleeping anymore, Brown refrains from drawing the faces of all the other girls he encounters.

/

The New York Times Book Review/

You don’t have to like comics to relish this book. Brown, whose previous work includes a comic-strip biography of the 19th-century Canadian revolutionary Louis Riel, begins his story in the summer of 1996, when his live-in girlfriend, Sook-Yin, confesses she has fallen for another guy. She also still wants to live with Chester. “I love living with you,” she says. Chester — feeling like his “normal, content, all-is-well-with-the-world self” — goes with the flow. (“You’re fine with this?” an astonished friend asks him. “I’m fine,” Chester replies.)

He and his girlfriend transition to being friends and housemates. A few months later, the new boyfriend moves in with them. Brown, still single, realizes he has come to a place in his life where he has “two competing desires — the desire to have sex, versus the desire NOT to have a girlfriend.” He seriously questions the idea of romantic love, and concludes it is a virtually impossible ideal. He decides to explore his options, which leads him to experiment with prostitutes. He finds some through brothel advertisements, and also online. “There are a whole bunch of these prostitute-review Web sites,” he tells a friend — johns writing for other johns, “like movie reviews or book reviews.”

Over the course of several years, Brown had numerous paid sexual encounters, and in “Paying for It” he has given each woman a chapter: Carla, Anne, Wendy, Yvette, back to Anne, Jolene, Larissa, Angelina, Kitty, Gwendolyn, Jenna, back to Angelina, Myra, etc. He also recounts conversations about his thoughts and motivations that he had with his close friends, some of whom disapprove (“There is NO way I’m paying for sex,” says one), others of whom are ambivalent (“I think it should be legal, but that’s not the same thing as saying it’s right”).

Chester Brown is not a john to pity. He has options. He is a reasonably handsome, lanky, talented artist, now 51 years old. Some women, and men, who read this memoir may develop a crush on this goodhearted bad boy. The cartoonist R. Crumb, who provides the introduction for the book, describes him as “a very advanced human.” Brown also seems to be a feeling, thoughtful, considerate man, honest with himself and others.

This graphic memoir is . . . sexually graphic. Chester’s penis is a leading character, and a charming one at that. Brown has made no obvious attempt to eroticize his drawings, and as a result his cartoons are totally sexy in the way real life and really good art are sexy. As he explores the logistics of being a john, he shares what he’s learned about hygiene, the etiquette of paying and tipping, and the necessary financial planning (“If I went every two weeks, that would be 26 times a year; 26 multiplied by $160 equals $4,160 a year — that’s quite a bit”). He also gratefully acknowledges the Canada Council for the Arts “for generously assisting me financially while I wrote and drew this work.” Can you imagine the National Endowment for the Arts financing any project remotely resembling this? O Canada!

MORE HERE/

Gunga Din

Gunga Din is a 1939 RKO adventure film directed by George Stevens and starring Cary Grant, Victor McLaglen and Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., loosely based on the poem of the same name by Rudyard Kipling combined with elements of his short story collection Soldiers Three. The film is about three British sergeants and Gunga Din, their native bhisti (water bearer), who fight the Thuggee, a cult of murderous Indians in colonial British India.

The supporting cast features Joan Fontaine, Eduardo Ciannelli, and, in the title role, Sam Jaffe. The epic film was written by Joel Sayre and Fred Guiol from a storyline by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, with uncredited contributions by Lester Cohen, John Colton, William Faulkner, Vincent Lawrence, Dudley Nichols and Anthony Veiller.

MORE HERE/

//

In the film, Jaffe brilliantly portrays Gunga Din, the slave/water boy, a native Hindu who desperately wants to be a "first class soldier" for the British army. He is soft spoken but intense with a deep longing to march in a soldier's uniform, do the maneuvers with them and be the bugler in the regiment. He is caught one day doing the maneuvers and holding a "stolen" bugle, by Sergeant Cutter. Cutter (Grant) is brave and fearless but he is also playful and comical. He befriends Din, instructs him privately with maneuvers and how to give a proper salute. He also lets Din keep his beloved bugle. He also calls the water boy "Bugler" much to Din's delight. Cutter is immensely proud to be a soldier of Her Majesty the Queen but he spends much of his time searching for buried treasure and gold. When we first meet up with Cutter and his two fellow soldiers in the movie, they are busy wrecking a village and throwing Scottish soldiers out of a window. These are the swindlers who sold Cutter a map to find emeralds. Unfortunately, he couldn't find his jewels but this is one of the film's funnier scenes. Later on, Din leads Cutter to a gold temple but instead of finding his fortune there, he may possibly meet his fate.

Cutter's partners in crime include MacChesney, the top sergeant played with the conventional brawn and enthusiasm that McLaglen possessed in all of his roles. MacChesney, known simply as "Mac" or sarcastically as "Cheesecake," laughs at Din's desire to be a first class soldier but the burly sergeant finds no humor for the very large soft spot that he has for Annie. Annie isn't his girlfriend but his pet elephant. In a very comical scene, Mac is taking care of Annie, who has developed some sort of ailment. He asks to see her tongue and she lifts her trunk up to him. He checks her forehead to see if she is feverish. When a comrade tells Mac that he'd like to try an old Indian remedy on the elephant, the sergeant complies. But, warns the comrade, very little medication must be given or the result can be fatal. He tries to give Annie a small spoonful of the elixir but she won't take it. Mac's paternal instincts come out and he gushes to Annie, "Go on now, you want your daddy to give you the medicine." He takes the spoonful of medicine and tells his "nice little elephant girl" that if she doesn't take it, she will never "grow up to be big and strong like Daddy." Sergeant Cutter passes by and suggests to him, "Maybe if Daddy takes a spoonful first, baby will do a patty-cake." Mac agrees with this and pretends to drink some of the liquid. Finally, Annie takes it, only to tumble down helplessly to the floor. Mac becomes nearly hysterical but thank God Annie sits up and regains her composure. Later on, this medication proves to be a big help during one of Mac and Cutter's schemes.

MORE HERE/

//

All movies, as a matter of fact, should be like the first twenty-five and the last thirty minutes of Gunga Din, which are the sheer poetry of cinematic motion. Not that the production as a whole leaves anything to be desired in lavishness and panoramic sweep. The charge of the Sepoy Lancers, for example, in the concluding battle sequence, is the most spectacular bit of cinema since the Warner Brothers and Tennyson stormed the heights of Balaklava. In fact the movies at their best really appear to have more in common with the poets than with plain, straightforward, rationally documented prose.

Though the picture draws heavily on the Ballads for atmosphere and inspiration, and doesn't scruple to use Kipling himself, the brilliantly talented young war correspondent, as a minor character (it seems he dashed off the famous poem in time for the Commandant to read it over the water carrier's grave), the only historical or literary authority for it seems to have been an original story by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur. In this case, "original" may be taken to signify that the story is quite unlike other predecessors in the same genre, except possibly The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, Beau Geste, The Lost Patrol, and Charge of the Light Brigade. The parallels—some of them doubtless unavoidable—may be charitably excused on the ground that two memories are better than one.

As for Gunga Din himself, it seems rather a pity that he should receive fourth billing in his own picture. Yet for all the dash cut by the three stars, Cary Grant, Victor McLaglen, and Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., it is the humble, ascetic, stooped, yet somehow sublime, figure of Sam Jaffe that one remembers. "An' for all 'is dirty 'ide, 'e was white, clear white, inside, when 'e went to tend the wounded under fire," said the poet, and the sentiment, Victorian and patronizing as it may be, echoes in the heart. There is infinite humility, age-old patience, and pity, in the way old Din kneels to offer water to the living and the dying. And, though bent under the weight of his perspiring water-skin, his agility in dodging bullets is marvelous to behold. As Sam Jaffe plays him, Gunga Din is not only a better man than any in the cast; he should be a serious contender for the best performance of the year.

MORE HERE/

The supporting cast features Joan Fontaine, Eduardo Ciannelli, and, in the title role, Sam Jaffe. The epic film was written by Joel Sayre and Fred Guiol from a storyline by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, with uncredited contributions by Lester Cohen, John Colton, William Faulkner, Vincent Lawrence, Dudley Nichols and Anthony Veiller.

MORE HERE/

//

In the film, Jaffe brilliantly portrays Gunga Din, the slave/water boy, a native Hindu who desperately wants to be a "first class soldier" for the British army. He is soft spoken but intense with a deep longing to march in a soldier's uniform, do the maneuvers with them and be the bugler in the regiment. He is caught one day doing the maneuvers and holding a "stolen" bugle, by Sergeant Cutter. Cutter (Grant) is brave and fearless but he is also playful and comical. He befriends Din, instructs him privately with maneuvers and how to give a proper salute. He also lets Din keep his beloved bugle. He also calls the water boy "Bugler" much to Din's delight. Cutter is immensely proud to be a soldier of Her Majesty the Queen but he spends much of his time searching for buried treasure and gold. When we first meet up with Cutter and his two fellow soldiers in the movie, they are busy wrecking a village and throwing Scottish soldiers out of a window. These are the swindlers who sold Cutter a map to find emeralds. Unfortunately, he couldn't find his jewels but this is one of the film's funnier scenes. Later on, Din leads Cutter to a gold temple but instead of finding his fortune there, he may possibly meet his fate.

Cutter's partners in crime include MacChesney, the top sergeant played with the conventional brawn and enthusiasm that McLaglen possessed in all of his roles. MacChesney, known simply as "Mac" or sarcastically as "Cheesecake," laughs at Din's desire to be a first class soldier but the burly sergeant finds no humor for the very large soft spot that he has for Annie. Annie isn't his girlfriend but his pet elephant. In a very comical scene, Mac is taking care of Annie, who has developed some sort of ailment. He asks to see her tongue and she lifts her trunk up to him. He checks her forehead to see if she is feverish. When a comrade tells Mac that he'd like to try an old Indian remedy on the elephant, the sergeant complies. But, warns the comrade, very little medication must be given or the result can be fatal. He tries to give Annie a small spoonful of the elixir but she won't take it. Mac's paternal instincts come out and he gushes to Annie, "Go on now, you want your daddy to give you the medicine." He takes the spoonful of medicine and tells his "nice little elephant girl" that if she doesn't take it, she will never "grow up to be big and strong like Daddy." Sergeant Cutter passes by and suggests to him, "Maybe if Daddy takes a spoonful first, baby will do a patty-cake." Mac agrees with this and pretends to drink some of the liquid. Finally, Annie takes it, only to tumble down helplessly to the floor. Mac becomes nearly hysterical but thank God Annie sits up and regains her composure. Later on, this medication proves to be a big help during one of Mac and Cutter's schemes.

MORE HERE/

//

All movies, as a matter of fact, should be like the first twenty-five and the last thirty minutes of Gunga Din, which are the sheer poetry of cinematic motion. Not that the production as a whole leaves anything to be desired in lavishness and panoramic sweep. The charge of the Sepoy Lancers, for example, in the concluding battle sequence, is the most spectacular bit of cinema since the Warner Brothers and Tennyson stormed the heights of Balaklava. In fact the movies at their best really appear to have more in common with the poets than with plain, straightforward, rationally documented prose.

Though the picture draws heavily on the Ballads for atmosphere and inspiration, and doesn't scruple to use Kipling himself, the brilliantly talented young war correspondent, as a minor character (it seems he dashed off the famous poem in time for the Commandant to read it over the water carrier's grave), the only historical or literary authority for it seems to have been an original story by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur. In this case, "original" may be taken to signify that the story is quite unlike other predecessors in the same genre, except possibly The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, Beau Geste, The Lost Patrol, and Charge of the Light Brigade. The parallels—some of them doubtless unavoidable—may be charitably excused on the ground that two memories are better than one.

As for Gunga Din himself, it seems rather a pity that he should receive fourth billing in his own picture. Yet for all the dash cut by the three stars, Cary Grant, Victor McLaglen, and Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., it is the humble, ascetic, stooped, yet somehow sublime, figure of Sam Jaffe that one remembers. "An' for all 'is dirty 'ide, 'e was white, clear white, inside, when 'e went to tend the wounded under fire," said the poet, and the sentiment, Victorian and patronizing as it may be, echoes in the heart. There is infinite humility, age-old patience, and pity, in the way old Din kneels to offer water to the living and the dying. And, though bent under the weight of his perspiring water-skin, his agility in dodging bullets is marvelous to behold. As Sam Jaffe plays him, Gunga Din is not only a better man than any in the cast; he should be a serious contender for the best performance of the year.

MORE HERE/

Persopolis

The Guardian Book Review/

The story begins with a young Marjane (or Marji), who doesn't understand what's going on around her. Her parents talk about dialectic materialism and martyrs. Her teacher says that the Shah is divine. Her maid doesn't eat with the family. Marjane herself wants to become a prophet. So she takes refuge in God and reading all the books she can.

And then the Shah is overthrown, and a new Islamic regime takes control. All the schools are single-gender, she is forced to wear a veil, and the picture of the Shah is torn out of her textbook. Her parents' friends, Siamak and Mohsen, are released from prison. She meets Anoush, her uncle whom she immediately loves. He tells her stories about being in prison and Russia, and gifts her with a bread swan.

Slowly, though, Marji and her parents realize that the regime isn't that much better than the monarchy that preceded it. Everyone who supported the revolution is now a sworn enemy of the government. The events that follow are unbelievable and, at times, horrifying. You'll have to read the rest and find out!

Satrapi wrote the text in an almost childish manner, to reflect Marjane's innocence in this horrifying world. All the characters are dynamic and realistic; I'll admit, I almost cried at a few moments in this book (and I never cry while reading books). The book moves at a fast pace, which almost gives the reader vertigo; the effect is very exhilarating.

MORE HERE>

//

The New York Times Book Review/

Marjane Satrapi's ''Persepolis'' is the latest and one of the most delectable examples of a booming postmodern genre: autobiography by comic book. All over the world, ambitious artist-writers have been discovering that the cartoons on which they were raised make the perfect medium for exploring consciousness, the ideal shortcut -- via irony and gallows humor -- from introspection to the grand historical sweep. It's no coincidence that one of the most provocative American takes on Sept. 11 has been Art Spiegelman's.

Like Spiegelman's ''Maus,'' Satrapi's book combines political history and memoir, portraying a country's 20th-century upheavals through the story of one family. Her protagonist is Marji, a tough, sassy little Iranian girl, bent on prying from her evasive elders if not truth, at least a credible explanation of the travails they are living through.

Marji, born like her author in 1969, grows up in a fashionably radical household in Tehran. Her father is an engineer; her feminist mother marches in demonstrations against the shah; Marji, an only child, attends French lycée. Satrapi is sly at exposing the hypocrisies of Iran's bourgeois left: when Marji's father discovers to his outrage that their maid is in love with the neighbors' son, he busts up the romance, intoning, ''In this country you must stay within your own social class.'' Marji sneaks into the weeping girl's bedroom to comfort her, reflecting, deadpan, ''We were not in the same social class but at least we were in the same bed.''

Marji finds her own solution, in religion, to the problem of social injustice. ''I wanted to be a prophet . . . because our maid did not eat with us. Because my father had a Cadillac. And, above all, because my grandmother's knees always ached.'' The book is full of bittersweet drawings of Marji's tête-à-têtes with God, who resembles Marx, ''though Marx's hair was a bit curlier.'' In upper-middle-class Tehran in 1976, piety is taken as a sign of mental imbalance: Marji's teacher summons her parents to discuss the child's worrying psychological state.

A few years later, of course, it's the prophets who are in power, and the lycée teachers who are being sent to Islamic re-education camp. Marji is 10 when the shah is overthrown, and she discovers that her great-grandfather was the last emperor of Persia. He was deposed by a low-ranking military officer named Reza, who, backed by the British, crowned himself shah. The emperor's son, Marji's grandfather, was briefly prime minister before being jailed as a Communist.

When the present-day shah is sent into exile, Marji's parents rejoice. Their Marxist friends and colleagues, freed from years in prison, come to the apartment for celebrations, at which they joke about their sessions with the shah's special torturers.

The nationwide jubilee is brief. Soon these same friends have been thrown back into jail or are murdered by the revolutionaries; Marji and her schoolmates take the veil and are taught self-flagellation instead of algebra. Those who can decamp for the West.

Once again, Marji finds herself a rebel, briefly detained by the Guardians of the Revolution for sporting black-market Nikes, in trouble at school for announcing in class that, contrary to the teacher's lies, there are a hundred times as many political prisoners under the revolution than there were under the shah. Once again, Marji notes, it's the poor who suffer: while Marji attends a ''punk'' party for which her mother has knitted her a sweater full of holes, peasant boys her age, armed with plastic keys promising them entry to paradise if they are killed, are being sent into battle in Iraqi minefields.

It is the war with Iraq that is this book's climax and turning point. Satrapi is adept at conveying the numbing cynicism induced by living in a city under siege both from Iraqi bombs and from a homegrown regime that uses the war as pretext to exterminate ''the enemy within.''

When ballistic missiles destroy the house next to Marji's, killing a childhood friend and her family, Marji's parents decide to send her abroad. The book ends with a 14-year-old Marji, palms pressed against the airport's dividing glass, her chador-framed face a mask of horror, looking back at her fainting mother and grieving father. ''It would have been better to just go,'' her older self concludes.

MORE HERE/

The story begins with a young Marjane (or Marji), who doesn't understand what's going on around her. Her parents talk about dialectic materialism and martyrs. Her teacher says that the Shah is divine. Her maid doesn't eat with the family. Marjane herself wants to become a prophet. So she takes refuge in God and reading all the books she can.

And then the Shah is overthrown, and a new Islamic regime takes control. All the schools are single-gender, she is forced to wear a veil, and the picture of the Shah is torn out of her textbook. Her parents' friends, Siamak and Mohsen, are released from prison. She meets Anoush, her uncle whom she immediately loves. He tells her stories about being in prison and Russia, and gifts her with a bread swan.

Slowly, though, Marji and her parents realize that the regime isn't that much better than the monarchy that preceded it. Everyone who supported the revolution is now a sworn enemy of the government. The events that follow are unbelievable and, at times, horrifying. You'll have to read the rest and find out!

Satrapi wrote the text in an almost childish manner, to reflect Marjane's innocence in this horrifying world. All the characters are dynamic and realistic; I'll admit, I almost cried at a few moments in this book (and I never cry while reading books). The book moves at a fast pace, which almost gives the reader vertigo; the effect is very exhilarating.

MORE HERE>

//

The New York Times Book Review/

Marjane Satrapi's ''Persepolis'' is the latest and one of the most delectable examples of a booming postmodern genre: autobiography by comic book. All over the world, ambitious artist-writers have been discovering that the cartoons on which they were raised make the perfect medium for exploring consciousness, the ideal shortcut -- via irony and gallows humor -- from introspection to the grand historical sweep. It's no coincidence that one of the most provocative American takes on Sept. 11 has been Art Spiegelman's.

Like Spiegelman's ''Maus,'' Satrapi's book combines political history and memoir, portraying a country's 20th-century upheavals through the story of one family. Her protagonist is Marji, a tough, sassy little Iranian girl, bent on prying from her evasive elders if not truth, at least a credible explanation of the travails they are living through.

Marji, born like her author in 1969, grows up in a fashionably radical household in Tehran. Her father is an engineer; her feminist mother marches in demonstrations against the shah; Marji, an only child, attends French lycée. Satrapi is sly at exposing the hypocrisies of Iran's bourgeois left: when Marji's father discovers to his outrage that their maid is in love with the neighbors' son, he busts up the romance, intoning, ''In this country you must stay within your own social class.'' Marji sneaks into the weeping girl's bedroom to comfort her, reflecting, deadpan, ''We were not in the same social class but at least we were in the same bed.''

Marji finds her own solution, in religion, to the problem of social injustice. ''I wanted to be a prophet . . . because our maid did not eat with us. Because my father had a Cadillac. And, above all, because my grandmother's knees always ached.'' The book is full of bittersweet drawings of Marji's tête-à-têtes with God, who resembles Marx, ''though Marx's hair was a bit curlier.'' In upper-middle-class Tehran in 1976, piety is taken as a sign of mental imbalance: Marji's teacher summons her parents to discuss the child's worrying psychological state.

A few years later, of course, it's the prophets who are in power, and the lycée teachers who are being sent to Islamic re-education camp. Marji is 10 when the shah is overthrown, and she discovers that her great-grandfather was the last emperor of Persia. He was deposed by a low-ranking military officer named Reza, who, backed by the British, crowned himself shah. The emperor's son, Marji's grandfather, was briefly prime minister before being jailed as a Communist.

When the present-day shah is sent into exile, Marji's parents rejoice. Their Marxist friends and colleagues, freed from years in prison, come to the apartment for celebrations, at which they joke about their sessions with the shah's special torturers.

The nationwide jubilee is brief. Soon these same friends have been thrown back into jail or are murdered by the revolutionaries; Marji and her schoolmates take the veil and are taught self-flagellation instead of algebra. Those who can decamp for the West.

Once again, Marji finds herself a rebel, briefly detained by the Guardians of the Revolution for sporting black-market Nikes, in trouble at school for announcing in class that, contrary to the teacher's lies, there are a hundred times as many political prisoners under the revolution than there were under the shah. Once again, Marji notes, it's the poor who suffer: while Marji attends a ''punk'' party for which her mother has knitted her a sweater full of holes, peasant boys her age, armed with plastic keys promising them entry to paradise if they are killed, are being sent into battle in Iraqi minefields.

It is the war with Iraq that is this book's climax and turning point. Satrapi is adept at conveying the numbing cynicism induced by living in a city under siege both from Iraqi bombs and from a homegrown regime that uses the war as pretext to exterminate ''the enemy within.''

When ballistic missiles destroy the house next to Marji's, killing a childhood friend and her family, Marji's parents decide to send her abroad. The book ends with a 14-year-old Marji, palms pressed against the airport's dividing glass, her chador-framed face a mask of horror, looking back at her fainting mother and grieving father. ''It would have been better to just go,'' her older self concludes.

MORE HERE/

Ernest and Celestine

Ernest & Celestine (French: Ernest et Célestine) is a 2012 French-Belgian animated comedy-drama film directed by Stéphane Aubier, Vincent Patar and Benjamin Renner. The film is based on a series of children's books of the same name published by the Belgian author and illustrator Gabrielle Vincent. The film was selected to be screened in the Directors' Fortnight section at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival, as part of the TIFF Kids programme at the 2012 Toronto International Film Festival and at the 2013 Hong Kong International Film Festival. It was selected for the grand competition at feature film edition of the 2013 World festival of animated film Animafest Zagreb and was screened as the opening film. The film was released in the United States in 2013 by GKIDS. There is also an English dub that was released on 28 February 2014, with the voices of Forest Whitaker, Mackenzie Foy, Lauren Bacall, Paul Giamatti, William H. Macy, Megan Mullally, Nick Offerman, and Jeffrey Wright. The film received widespread critical acclaim, and became the first animated film to win the Magritte Award for Best Film.

More Here.

More Here.

Reflected in Water

There is more to Goa than sun and sand, the hippies and the fanny, and Portuguese influence and the stately churches. It’s all these and more. It is a tiny geographical land which has been constantly struggling to maintain its own identity, first with the forces of the Portuguese colonialists and then, after the liberation, with the Indian state, as Maharashtra first annexed the state to its borders and then tried to impose Marathi as the official language, as opposed to the local Konkani.

The book, incisively edited by Jerry Pinto, is a precious mixture of critical essays, book extracts, commentary, poetry and even a comic strip, ruminating the past, present and future of Goa, how it came into being as a result of the old marriage between Konkani and Portuguese, and how it fought hard to retain its own identity, first at the hands of the Portuguese, and then, the Indian state, and now, the onslaught of globalization.

Among other things, I did love the placement of two contradictory pieces together. First, an extract from William Dalrymple and second, Prabhakar S Angle’s defence of the misrepresentation of Goa.

The book, incisively edited by Jerry Pinto, is a precious mixture of critical essays, book extracts, commentary, poetry and even a comic strip, ruminating the past, present and future of Goa, how it came into being as a result of the old marriage between Konkani and Portuguese, and how it fought hard to retain its own identity, first at the hands of the Portuguese, and then, the Indian state, and now, the onslaught of globalization.

Among other things, I did love the placement of two contradictory pieces together. First, an extract from William Dalrymple and second, Prabhakar S Angle’s defence of the misrepresentation of Goa.

Monday, June 09, 2014

The Third Testament

The official blurb/

A monastery is burned to the ground; every monk within killed. It now falls to Conrad of Marburg, a disgraced Inquisitor, to discover the motive for this heinous crime and make sure that those responsible are punished...

But his journey into darkness is only beginning!

A medieval thriller and a swashbuckling 14th century relic quest - Indiana Jones meets The Name of the Rose!

The real Conrad/

Konrad von Marburg (sometimes anglicised as Conrad of Marburg; (Born 1180-died 30 July 1233) was a medieval, German priest and nobleman. He was commissioned by the pope to combat the Albigensians.

Konrad von Marburg is pictured as the main character in the French comic strip "The Third Testament" by Xavier Dorison and Alex Alice. After hiding for 20 years after being sentenced to death by an Inquisition Tribunal framed by Henry of Sayn, a mellowed and weary Konrad again faces the mysterious Count of Sayn in a race to find a legendary document, the “Third Testament”. The story is a 4-part suite published by Glénat.

MORE HERE/

A monastery is burned to the ground; every monk within killed. It now falls to Conrad of Marburg, a disgraced Inquisitor, to discover the motive for this heinous crime and make sure that those responsible are punished...

But his journey into darkness is only beginning!

A medieval thriller and a swashbuckling 14th century relic quest - Indiana Jones meets The Name of the Rose!

The real Conrad/

Konrad von Marburg (sometimes anglicised as Conrad of Marburg; (Born 1180-died 30 July 1233) was a medieval, German priest and nobleman. He was commissioned by the pope to combat the Albigensians.

Konrad von Marburg is pictured as the main character in the French comic strip "The Third Testament" by Xavier Dorison and Alex Alice. After hiding for 20 years after being sentenced to death by an Inquisition Tribunal framed by Henry of Sayn, a mellowed and weary Konrad again faces the mysterious Count of Sayn in a race to find a legendary document, the “Third Testament”. The story is a 4-part suite published by Glénat.

MORE HERE/

Queen

Queen is not a great film, but a smart one. The makers, the writers and the directors know their craft, and their movies, especially a typical coming-of-age film. And, here, they try to avoid clichés while telling a story which is nothing but clichés. So, clichés are unavoidable (like a food-loving loud Italian, garrulous Punjabis, Bollywood songs in a French disco…).

It doesn’t matter. What matters how the film treats its central character, the smart dialogues and finally, the how the film ends, happily, but not with happily ever after, and not in a wedding, of course.

The wedding comes as the film begins and it is aborted, as Rani’s intended Vijay develops a cold feat realizing how middle class his girlfriend was. The brokenhearted but feisty Delhi girl, Rani, decides to go on a honeymoon nonetheless, because she always wanted to go to Paris and she bought the tickets on her own money. So begins the journey of Rani’s self-realisation, at the end of which she will come to appreciate her own worth. Before that, however, she has to fight the memory of her lost love and meet new people in a strange world, which does not speak English, not that Rani speaks English either.

There is actually no story in Queen, but a series of vignettes, a series of montages set to music, with Amit Trivedi (and others) humming in the background, broken by a series of scenes. It is a wonder that the film works, but it does, and it does wonderfully. For this, first, the credit goes to the screenwriter, who shows remarkable restrain in delineating Rani’s growth. Though it is a story of Rani’s change, she doesn’t change overnight and completely. At the end, she is a changed person, yet, she remains the same girl. For a Hindi movie, this is truly remarkable. Second, the editing, not single scene drags. It ends where it should. Observe how the flashback of Rani’s love story is used. I also liked the scene of Rani being chased by the Eifel Tower. Third, the performance of Kangana Ranaut as Rani. She makes Rani as a middle class Delhi girl believable. Observe, how she says, ‘lip-to-lip kiss’.

I also liked how the film twists the clichés. Instead of going to the regular haunts of a Hindi movie (from Switzerland to London to Sidney) the film goes to Paris (Priety Zinta must be fuming!). And, instead of Hindi-speaking white extras like other films, we have characters from France, Russia, Japan and Italy, none of whom can speak good English, let alone Hindi. But the movies refuses to take a short cut, and let them converse in their half-known languages. Which is fun and refreshing. Also observe how the pole dancer Roxette AKA Rukshar speak such chaste Urdu, which is almost unnerving to listen to. And, to called the half-French girl Vijaylaxmi was a stroke of genius.

It doesn’t matter. What matters how the film treats its central character, the smart dialogues and finally, the how the film ends, happily, but not with happily ever after, and not in a wedding, of course.

The wedding comes as the film begins and it is aborted, as Rani’s intended Vijay develops a cold feat realizing how middle class his girlfriend was. The brokenhearted but feisty Delhi girl, Rani, decides to go on a honeymoon nonetheless, because she always wanted to go to Paris and she bought the tickets on her own money. So begins the journey of Rani’s self-realisation, at the end of which she will come to appreciate her own worth. Before that, however, she has to fight the memory of her lost love and meet new people in a strange world, which does not speak English, not that Rani speaks English either.

There is actually no story in Queen, but a series of vignettes, a series of montages set to music, with Amit Trivedi (and others) humming in the background, broken by a series of scenes. It is a wonder that the film works, but it does, and it does wonderfully. For this, first, the credit goes to the screenwriter, who shows remarkable restrain in delineating Rani’s growth. Though it is a story of Rani’s change, she doesn’t change overnight and completely. At the end, she is a changed person, yet, she remains the same girl. For a Hindi movie, this is truly remarkable. Second, the editing, not single scene drags. It ends where it should. Observe how the flashback of Rani’s love story is used. I also liked the scene of Rani being chased by the Eifel Tower. Third, the performance of Kangana Ranaut as Rani. She makes Rani as a middle class Delhi girl believable. Observe, how she says, ‘lip-to-lip kiss’.

I also liked how the film twists the clichés. Instead of going to the regular haunts of a Hindi movie (from Switzerland to London to Sidney) the film goes to Paris (Priety Zinta must be fuming!). And, instead of Hindi-speaking white extras like other films, we have characters from France, Russia, Japan and Italy, none of whom can speak good English, let alone Hindi. But the movies refuses to take a short cut, and let them converse in their half-known languages. Which is fun and refreshing. Also observe how the pole dancer Roxette AKA Rukshar speak such chaste Urdu, which is almost unnerving to listen to. And, to called the half-French girl Vijaylaxmi was a stroke of genius.

Mud

The Guardian Movie Review/

Jeff Nichols's exhilarating third movie, Mud, concerns two 14-year-old boys growing up in a small town beside the Mississippi in the director's native south central state of Arkansas, and it's impossible while watching it not to think about Huckleberry Finn and Hemingway's claim for its essential position in the experience of growing up close to the American landscape. It also brings to mind Hemingway's own detailed, tactile descriptions of fishing, sailing, hunting and living close to nature in the wild. There's another great novel about growing up, understanding and misunderstanding the world that Mud inevitably evokes. That's Great Expectations and Pip's relationship with fugitive convict Magwitch.

Nichols's Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer are Ellis (Tye Sheridan) and Neckbone (Jacob Lofland) who set off on an adventure down river to find an old boat, surrealistically stranded high in a tree on a deserted island. They come across a handsome, charismatic man called Mud (Matthew McConaughey), and he too lays claim to the boat. When it transpires he's on the run for what he claims to be a justified homicide down in Texas, the boys enter into a pact to provide him with food and help him restore the craft as a means of escape. Ellis acts out of an innate sense of decency, sympathy and a need for friendship. Neckbone's motives are initially cynical and mercenary, though he gradually warms to the outsider.

In a deft piece of storytelling Nichols first links the tasks the boys undertake to their troubled family lives. Then he brings in Tom (Sam Shepard), the taciturn loner and former marine living on a houseboat across the river who has a key relationship to Mud. And finally their fates are dramatically involved with the strangers in town attracted by Mud: his mysterious girlfriend Juniper (Reese Witherspoon) and the posse of bounty hunters led by the patriarchal King (Joe Don Baker).

Through Ellis's wondering, romantic eyes we see the mighty river, which represents adventure, unknown dangers and the promise of a journey to a world elsewhere. He longs for love, friendship and security, but his parents' marriage is breaking up and their houseboat, from which his father conducts his business as hunter and fisherman, is threatened with confiscation. He envies the orphaned Neckbone's lovably wild uncle (Michael Shannon) who dives for clams wearing a homemade outfit that looks like Ned Kelly's improvised armour.

MORE HERE/

Jeff Nichols's exhilarating third movie, Mud, concerns two 14-year-old boys growing up in a small town beside the Mississippi in the director's native south central state of Arkansas, and it's impossible while watching it not to think about Huckleberry Finn and Hemingway's claim for its essential position in the experience of growing up close to the American landscape. It also brings to mind Hemingway's own detailed, tactile descriptions of fishing, sailing, hunting and living close to nature in the wild. There's another great novel about growing up, understanding and misunderstanding the world that Mud inevitably evokes. That's Great Expectations and Pip's relationship with fugitive convict Magwitch.

Nichols's Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer are Ellis (Tye Sheridan) and Neckbone (Jacob Lofland) who set off on an adventure down river to find an old boat, surrealistically stranded high in a tree on a deserted island. They come across a handsome, charismatic man called Mud (Matthew McConaughey), and he too lays claim to the boat. When it transpires he's on the run for what he claims to be a justified homicide down in Texas, the boys enter into a pact to provide him with food and help him restore the craft as a means of escape. Ellis acts out of an innate sense of decency, sympathy and a need for friendship. Neckbone's motives are initially cynical and mercenary, though he gradually warms to the outsider.

In a deft piece of storytelling Nichols first links the tasks the boys undertake to their troubled family lives. Then he brings in Tom (Sam Shepard), the taciturn loner and former marine living on a houseboat across the river who has a key relationship to Mud. And finally their fates are dramatically involved with the strangers in town attracted by Mud: his mysterious girlfriend Juniper (Reese Witherspoon) and the posse of bounty hunters led by the patriarchal King (Joe Don Baker).

Through Ellis's wondering, romantic eyes we see the mighty river, which represents adventure, unknown dangers and the promise of a journey to a world elsewhere. He longs for love, friendship and security, but his parents' marriage is breaking up and their houseboat, from which his father conducts his business as hunter and fisherman, is threatened with confiscation. He envies the orphaned Neckbone's lovably wild uncle (Michael Shannon) who dives for clams wearing a homemade outfit that looks like Ned Kelly's improvised armour.

MORE HERE/

Kill Your Darlings

Another lover hits the universe

The circle is broken

But with death comes rebirth

And like all lovers and sad people

I am a poet…

The young Allen Ginsberg, finding a resolution after the dramatic events during his days in Columbia University, which ended with ‘the night in question,’ Daniel Radcliffe in John Krokidas’s Kill Your Darlings (2013)

Gulaab Gang

I love me some action heroine films. You know, I really, really love Lara Croft and Kill Bill. You get the drift. So I had to go and watch Gulaab Gang, especially when I really, really love Juhi Chawla. Here, gossip rags said, she was in utter villainous mode. I had to go and see it. I did not care much about Madhuri though. Never had. But the film was touted as an action extravaganza between Madhuri and Juhi, former rivals to the top heroine rat race.

The film begins well, focusing on the issues of the aam aadmi, paani, bijli, anaaj and so on, especially issues concerning women. The do-gooder heroine really wants a school for the girls. As the film progresses, however, it is mired in petty, dirty politics, interspersed with scenes borrowed from B-Grade Hindi films, both literally and figuratively.

I did not have problems with Madhuri’s murderous intentions and her Tonny Ja action avatar, which are quite entertaining in a camp way, but when Juhi picks up a machine gun in the middle of a holi song, it was just too incongruous.

Then there were the stupid dances and those forgettable songs. It’s a Madhuri film, so there had to be dances. Still they feel like torture, even more tortuous than the tacky exchanges of dialogues between the politician and the activist. For an apparent issue-based film, the dialogues are really corny, especially those given to Juhi’s politician, as if they were written for somebody in a film starring Akshay Kumar directed by Prabhu Deva. It’s to Juhi’s credit that she does a fine job with it.

I think I can empathize with the writer of the film, who is also the director, Soumik Sen. The sole point of the film was to mount a rousing conflict between the characters played by Madhuri and Juhi, the female Robin Hood of the badlands and the vile politician archetype. Sen uses every device at his disposal to make it happen, even at times, at the expense of the narrative. The whole election rigmarole was a utter nonsense.

More deplorable still is how the other characters are relegated to the sidelines. The best characters of the film are played by Priyaka Bose, with her smoldering sensuality and by Divya Jagdale, with her tomboy antics. When you wanted to see more of them, the film decides to bump them off, quite ingloriously. I would have loved to see more of Jagdale and her boatman lover. I would have loved to see more of Bose, who really smolders. She is the most convincing action heroine in the film and when is offed ingloriously, the film was lost to me.

And oh, don’t get me started on the foolish flashbacks. This is what I call immediate flashback, or flashback for fools. Every time, the film’s good guys take revenge on a bad guy, the scene cuts to a sepia-tonned flashback, to remind the audience why the bad guy is being punished. Note to the film’s editor: Audiences are not idiots, you know. If you think, we won’t get the message, then something is wrong with your film, don’t blame us.

The film begins well, focusing on the issues of the aam aadmi, paani, bijli, anaaj and so on, especially issues concerning women. The do-gooder heroine really wants a school for the girls. As the film progresses, however, it is mired in petty, dirty politics, interspersed with scenes borrowed from B-Grade Hindi films, both literally and figuratively.

I did not have problems with Madhuri’s murderous intentions and her Tonny Ja action avatar, which are quite entertaining in a camp way, but when Juhi picks up a machine gun in the middle of a holi song, it was just too incongruous.

Then there were the stupid dances and those forgettable songs. It’s a Madhuri film, so there had to be dances. Still they feel like torture, even more tortuous than the tacky exchanges of dialogues between the politician and the activist. For an apparent issue-based film, the dialogues are really corny, especially those given to Juhi’s politician, as if they were written for somebody in a film starring Akshay Kumar directed by Prabhu Deva. It’s to Juhi’s credit that she does a fine job with it.

I think I can empathize with the writer of the film, who is also the director, Soumik Sen. The sole point of the film was to mount a rousing conflict between the characters played by Madhuri and Juhi, the female Robin Hood of the badlands and the vile politician archetype. Sen uses every device at his disposal to make it happen, even at times, at the expense of the narrative. The whole election rigmarole was a utter nonsense.

More deplorable still is how the other characters are relegated to the sidelines. The best characters of the film are played by Priyaka Bose, with her smoldering sensuality and by Divya Jagdale, with her tomboy antics. When you wanted to see more of them, the film decides to bump them off, quite ingloriously. I would have loved to see more of Jagdale and her boatman lover. I would have loved to see more of Bose, who really smolders. She is the most convincing action heroine in the film and when is offed ingloriously, the film was lost to me.

And oh, don’t get me started on the foolish flashbacks. This is what I call immediate flashback, or flashback for fools. Every time, the film’s good guys take revenge on a bad guy, the scene cuts to a sepia-tonned flashback, to remind the audience why the bad guy is being punished. Note to the film’s editor: Audiences are not idiots, you know. If you think, we won’t get the message, then something is wrong with your film, don’t blame us.

Sunday, June 08, 2014

Frida

Everyone tells me the dark, sad one,

Dark but affectionate

I'm like the green chili, sad one

Spicy but tasty

Woe is me, sad one, sad one, sad one

Carry me to the river

Cover me with your wrap, sad one

I'm freezing to death.

I love you, do you want, sad one

Do you want me to love you more?

If I've already given you life, sad one

What more do you want?

Original Spanish, badly (of course) translated into English, from the soundtrack of Julie Taymor’s Frida (2002)

One Hundred Years of Solitude

I have read the novel, One Hundred Years of Solitude, a thousand times. I have two dog-eared copies of the book. After Gabriel Garcia Marquez passed away recently, I decided to read the book again, from the very first page.

You see, since my first reading of the book, I have never ventured into it in chronological order. You just open a page, at random, and the magic of the book will take you in. In the past 10 years since I last read the book, the magic has not diminished. The prose never fails to evoke emotions. And the characters, each with his/her tragic idiosyncrasies, are like old friends.

Reading the novel again, however, confirmed two of my pet peeves about the book.

First, the need for paragraphs. The book certainly needs more paragraphs. Sometimes a paragraph goes on for more than two pages, and they relate to various different things. So, dividing them into paragraphs should be a logical option. Even stylistically, I do not think such long paragraphs are desired.

Second, I had problem with how the narrator suddenly jump from one incident to another, just when the incident in question was getting more interesting, sometimes at the expense of jumbling things up. This is one of the reasons why many new readers find it difficult to enter into its magical world. No, it’s not really a complaint. For me, this jumbling up of events works well. Only, I wish there were more descriptions.

There are just few descriptions in the books, though they are all undeniably enchanting. That is why you hanker after more. But it doesn’t come. In the middle of the book, after the disastrous affair with the butterfly man, Fernanda takes Meme away from Macondo in a train. Here Marquez describes in a few lines the scene seen from the window of the train.