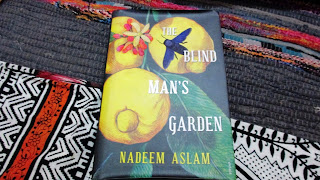

In Nadeem Aslam's memorable 2008 novel The Wasted Vigil, set in Afghanistan, beauty and pain were intimately entwined, impossible to keep apart. The various incompatibles in his new book The Blind Man's Garden don't surrender their separateness so magically. There are awkward gaps and residues despite the author's great gifts of imagination.

The novel starts in late 2001 and takes place largely in Pakistan, though some sections are again set in Afghanistan, newly invaded. Elderly Rohan, eventually the blind man of the title, his vision gradually dimming, founded an Islamic school called Ardent Spirit with his wife Sofia. After her death he was forced out as the school became intolerant, a virtual nursery of jihad, but continues to live in the house that he built on the same site.

The main characters of The Wasted Vigil were non-natives, a Briton, an American and a Russian (partial roll call of the nationalities that have meddled in Afghanistan). There are no such mediating figures in the new novel, and they are missed. No doubt imperialistic reading habits die hard, the easy expectation of having otherness served up on a plate, but it's not just that. For Nadeem Aslam to communicate the richness and depth of his characters' culture, he must keep touching in the background they take for granted, in passages that float free of their points of view. He informs us for instance that orphaned children are likely to be sought out and asked to say prayers, since they belong to a category of being whose requests Allah never ignores, and that the Angel of Death is said to have no ears, to prevent him from hearing anyone's pleas. When there's a reference to mountains near Peshawar being "higher than the Alps placed onto the Pyrenees", the European frame of reference is jarring.

Before the main characters are properly introduced a minor figure administers a distracting overdose of symbolism. A "bird pardoner" sets up snares in the trees of Rohan's garden, trapping the birds in nooses of steel wire. He plans to sell them in the town, since freed birds say prayers on behalf of those who buy their freedom. He doesn't come back, though, at the promised time, and the trees are full of suffering birds.

Another minor character is a mendicant who goes around wrapped in hundreds of chains. The idea is that each link represents a prayer, and disappears as Allah grants it. The book also contains a ruby that appears without explanation, just in time to ransom a prisoner from a warlord, though the warlord, taking offence at a lack of respect during the ransoming process, pulverises the jewel and uses it as an instrument of torture instead.

More here/

/

IN NADEEM ASLAM’s haunting new novel, The Blind Man’s Garden, a village schoolteacher in Afghanistan writes to the United Nations pleading to be rescued from the hell she is in: “It is my 197th letter over the past five years, please help us.” The letter is written four years into the Taliban’s regime of stonings and public beheadings; a regime with a special affection for female schoolteachers depraved enough to educate young girls.

Where did this teacher get the money for foreign postage for 197 letters, one wonders. To whom in the UN did she address her entreaties? Did anyone in that noble and oily organization ever read her letters? The reader is not told any of this. Mikal, the novel’s intense young protagonist, finds the letter after 9/11, torn in half in a rose garden in a Taliban mountain fort, hours before it is stormed by American soldiers. To yoke beauty and brutality by locating a paradisiacal rose garden and stream inside a compound of zealots is a hallmark of Aslam’s lyrical style. He is a writer who can bend barbed wire into calligraphy. In his second and most deeply written novel, Maps for Lost Lovers, Pakistani immigrants in an English village place pots of scented geraniums in the center of the downstairs room in the hope that if white racists were to break in at night, the perfume of “rosehips and ripening limes” from the smashed pots would warn the sleepers of intruders. Rose gardens in Taliban citadels might sound like a touch of orientalist rogue, but to mull over the image is to discern an imperceptible hint: isn’t another rose garden the site from which a succession of presidents have declared war and missile strikes, and lied to the world? There is no direct equivalence here — Aslam is neither a pamphleteer nor a fool — but he certainly startles the reader into looking at the world with new eyes. This is a guerilla wordsmith who takes cover behind loveliness to lob language at your certainties.

Mikal and his best friend travel up from Pakistan to provide medical aid to the wounded people of Afghanistan but are duped and sold to the Taliban. An ordinary man caught in the Great Game, Mikal is described as “a mud-child and drifter,” for that is what his life has been ever since his beloved father, a communist poet, was disappeared by a Pakistani dictator. The figure of the persecuted poet recurs through Aslam’s fiction, no doubt in homage to his own father, a poet forced to seek asylum in England from the pro-American General Zia. Mikal’s journey will propel the narrative; illuminate the horrors of the Taliban’s intolerance and America’s blundering war on terror. He will blunder terribly too, even as he tries to protect with maimed hands (his index fingers have been chopped off by an Afghan warlord to impede him from using a gun) the destinies of those around him: his best friend who is with him in that rose garden fortress; his best friend’s wife whom he loves with a blazing passion; his irreverent and wonderful brother, Basie, named for the Count of jazz; and the silent American soldier who has the word “Infidel” tattooed on his back like a tabloid taunt, not in English, but in huge Arabic letters, so that the enemy can read and know that America is unafraid.

More here/

No comments:

Post a Comment